Liveable Neighborhoods

A New City and Century – Utopian Dream Realized in the Outside Lands West of Twin Peaks

“The turn of the century was a period of transition and momentous change. These years witnessed the beginning of some of the great innovations and themes of the twentieth century, and in these, California, was an active participant, contributor, and leader. Automobiles were taking to the roads, advances were being made in industry and agriculture, cities were being illuminated with electricity, the arts were shaking loose of long-held ideals, and conservationists were becoming increasingly concerned about the environment…San Francisco, the state’s most populous city, had reached 350,000, and Los Angeles surpassed 100,000.” (California History Fall 2000.)

Gallery

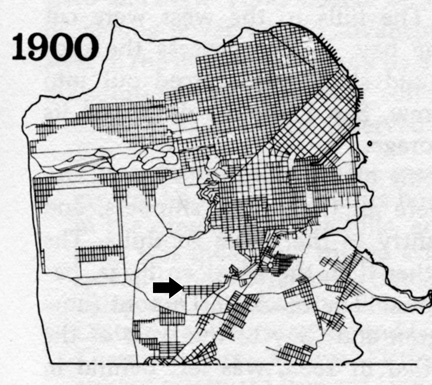

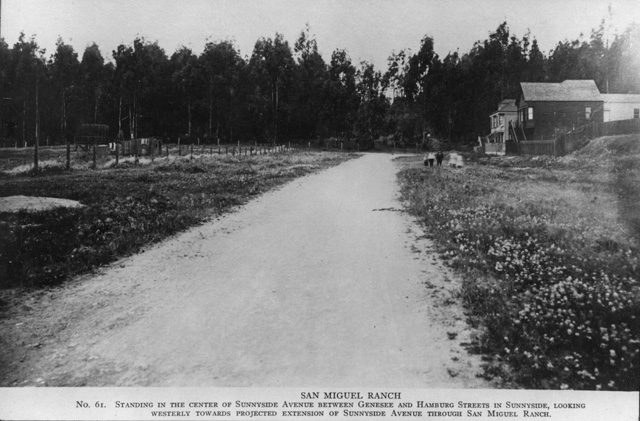

By 1900, the Sunnyside District has been constructed as far east as Hamburg Street and A.S. Baldwin was in court to develop the area west and north of it after the death of Adolph Sutro. Rogers and Stone Company advertised lots for sale in Sunnyside, “a sheltered location near the great Sutro Forest in the center of San Francisco” in 1909 for $400-$600. (Courtesy San Francisco Planning Department.)

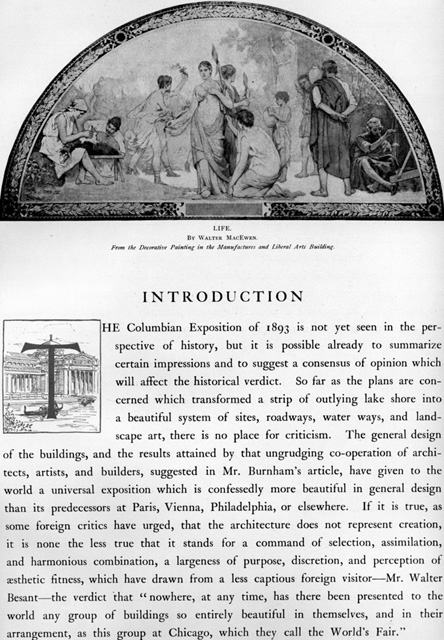

Daniel Burnham architectural design for Chicago’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 started a revolution in city planning across the country – the City Beautiful movement. Historian Cameron Binkley writes, “Driven by the ethos of middle class environmentalism, and aesthetics expressed as beauty, order, system, and harmony…City Beautiful enthusiasts promoted the creation of monumental public structures and park-like boulevards, the adoption of neoclassic and naturalistic designs in civic architecture, and the use of modern methods of urban planning and sanitary engineering. Rarely credited, female adherents were especially active in planting trees and flowers; promoting parks and playgrounds; cleaning up garbage; regulating utility poles, billboards, and nuisance industries; and promoting zoning restrictions. This work combined women’s interests in nature, art, health, and society.” In his 1905 City Beautiful Plan for San Francisco, Daniel Burnham recommended hilltops remain free of development, underground transit through them to the West of Twin Peaks, where streets would gently follow the natural contours of the land. (Author’s Collection.)

The Quast family took this picture just after the 1906 Earthquake and before the building was further destroyed by fire. A road builder, future resident of Ingleside Terraces, Jack Granfield, resourcefully used bricks from City Hall afterwards to repair city streets. He also did much of the pavement work in Golden Gate Park, despite legendary disputes with the Superintendent, John McLaren, (on whose birthday Mount Davidson Park was dedicated). (Courtesy Jeanne Davis MacKenzie.)

Architect George Kelham‘s professional education was received at Harvard and L’Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. In 1898 he entered the employ of Trowbridge and Livingston in New York and was sent by that firm in 1908 to oversee the construction of a new Palace Hotel to replace the one destroyed in the earthquake and fire. In 1916, he wins the competition to build the new City’s Main Library on the former site of the City Hall after it is rebuilt on Polk Street.

View of Twin Peaks traversed by Corbett Avenue and downtown San Francisco from the west on Mount Davidson in 1905. The Sierra Club asked the city to name the mountain for one of their charter members, George Davidson, in 1910. After the club announced that the program would be delayed because of a storm, Dr. Alexander G. McAdie, chief of the U.S Weather Bureau in San Francisco declared: “Postpone it if you wish, but I will be there.” Standing alone, he delivered his address to the wind and the rain and proclaimed the new name Mount Davidson.

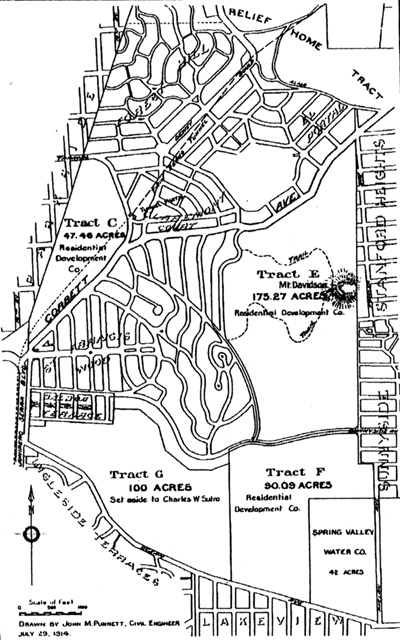

A.S. Baldwin’s plan for Adolph Sutro’s property included the extension of Sunnyside Avenue past Hamburg Street through “The Great Sutro Forest” all the way to the old Ingleside Racetrack (visible below). In partnership with Howell, their Residential Development Corporation bought 724 acres for $1,417,877 in 1911. (Courtesy Ken Hoegger and Miraloma Park Improvement Club.)

The effort to quickly rebuild the city after the 1906 Earthquake put Burnham’s City Beautiful Plan on the back burner. Many residents left the city all together for suburbs being built on the Peninsula, East Bay, and Marin. The Chronicle reported on April 25, 1906, that the San Francisco Real Estate Board had greatly augmented its membership since the fire. J.R. Howell, chair, was directed to ask the Mayor to organize a committee to which all matters relating to the layout of a new San Francisco shall be referred. “It was agreed that the calamity should be spoken of as ‘the great fire,’ and not as ‘the great earthquake.’” Howell’s partner, A.S. Baldwin proceeded to utilize elements recommended by Burnham as a marketing tool to bring people to his “suburbs in the city” West of Twin Peaks. New homes in Balboa Terrace, Ingleside Terraces, Mount Davidson Manor, Westwood Highlands, Monterey Heights Sherwood Forest, Miraloma Park, and Westwood Park, were built to preserve the views and sunlight afforded by Mount Davidson’s hillside settings, as well as, the abundant greenery of Sutro’s forest, seen above and on the right above Islais Creek and the Geneva Carbarn. (Courtesy Ken and Kathy Hoegger.)

Mt. Davidson seen in the background of these two photos. Left is the “new” 1912 streetcar 206 on San Jose Avenue April 24, 1913. Right are the horses at the new shop construction site on Geneva Avenue Nov. 2, 1906. (Image # U03948/U01028 | Images Courtesy of the SFMTA Photo Archive | SFMTA.com/photo).

The subdivision map for Balboa Terrace was created in 1912. Adjacent to St. Francis Wood, with large entrance gates and a central landscaped pedestrian parkway, it was built by Lang Realty with Harold G. Stoner as supervising architect. Architect Patrick McGrew writes of these new neighborhoods being created west of Twin Peaks, “Between the years 1900-1915, without any government intervention or direct support, thousands of San Francisco’s most beautiful homes were built, creating dozens of the city’s most attractive neighborhoods…These homes will never be found in the tourist brochures that describe the sites of San Francisco, for none are located in the tourist zone… These are the homes where San Franciscans live – a “Home City – a good place in which to live,” in the words of the 1915 Chamber of Commerce Publication.”

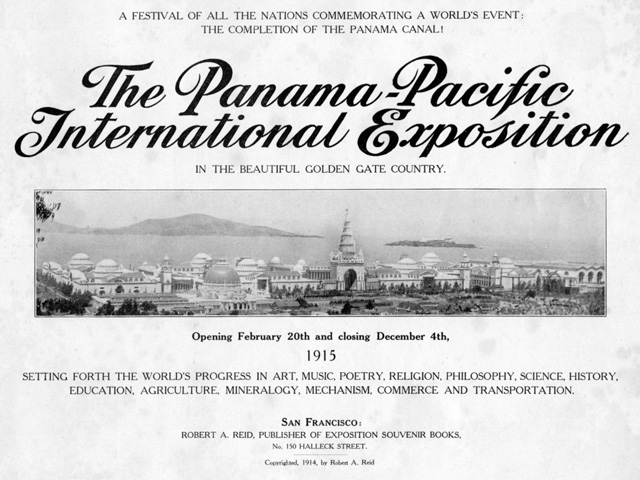

In 1912, George Kelham was appointed Chief of Architecture for San Francisco’s 1915 Pan American International Exposition to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal and to show the world it has recovered from the earthquake devastation. (Courtesy Ron Davis.)

Fifteen hundred people attended an opening ceremony on October 13, 1913, at Ingleside Terraces for the 28-foot high marble and concrete building of the world’s largest sundial to commemorate the opening of the Panama Canal. (Courtesy Margie Whitnah.)

Westwood Park created in 1917 by Baldwin and Howell for families of average means, featured bungalow Arts and Crafts architecture by Charles Strothoff and Ida McCain. The entrance gates were designed by Louis Christian Mullgardt, architect for 1915 Pan Pacific International Exposition. The City appointed its first Planning Commission in 1917 to implement land use controls and establish separate zones for residential, commercial, and industrial uses.(Courtesy Westwood Park Association.)

Like Adolph Sutro, A. S. Baldwin struck it rich with a tunnel. The extension of the streetcar line from downtown 12,000 feet below Twin Peaks to West Portal, the longest municipally owned tunnel (2.25 miles) devoted to rapid transit, of its time, would dramatically improve sales of his new home sites around Mount Davidson. As Mayor “Sunny Jim” Rolph remarked at dedication ceremonies for the Twin Peaks Tunnel on July 14, 1917: “Westward the course of Empire takes its way.” (Courtesy Ken Hoegger.)

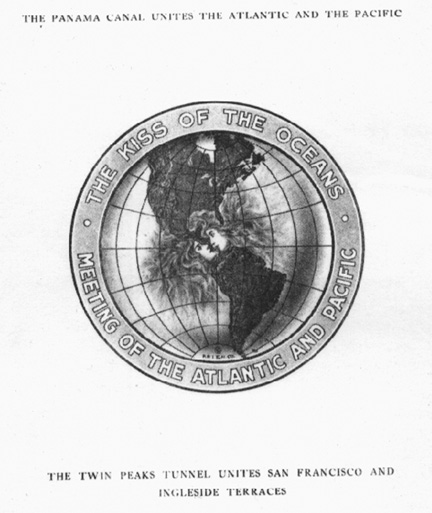

Ingleside Terraces brochure, “The Panama Canal unites the Atlantic and the Pacific, the Twin Peaks Tunnel unites San Francisco and Ingleside Terraces.” “Historic coincidences are sometimes significant. Just why the final blast at Panama, that permitted the waters of the Atlantic and the Pacific to intermingle, should occur on the same day that the Sundial at Ingleside was dedicated may not be at first apparent, but the ‘kiss of the oceans,’ promise of the coming greatness of San Francisco, needed as a complement and some assurance of the fitting homes required for its happiness and highest welfare.” (Courtesy Margie Whitnah.)

For a decade, Mayor James Rolph and City Engineer Michael O’Shaughnessy designed and constructed a network of boulevards in the undeveloped western half of the city. The opening of Sloat Boulevard in 1919 further improved the accessibility to Balboa and Ingleside Terrace subdivisions. (Courtesy Ken Hoegger.)

Next: Chapter 3 Women’s Suffrage, Temperance Movement, and Prohibition – Daring to Dream