Madie Brown

“As chairman of arrangements, I have dared to dream that our President would press the button in Washington, D.C., which in turn would light for the first time this giant cross in San Francisco. It seems most appropriate that the President, who has brought light to many a darkened American home and who through his New Deal has instilled the principles of the Golden Rule into American business, should take part in this cross-lighting ceremony.”

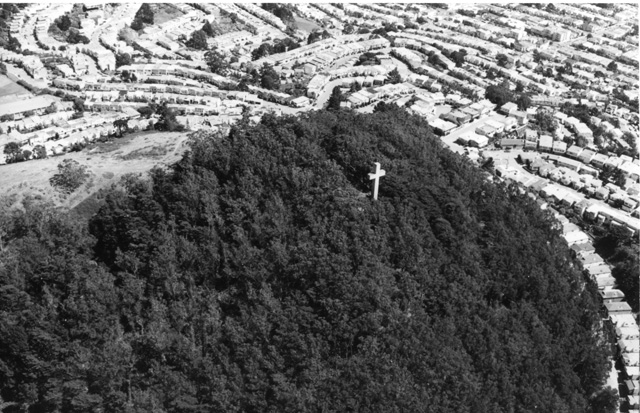

Mrs. Edmund N. “Madie” Brown wrote these words to President Roosevelt in 1934 just before the International Longshoremen’s Union, led by labor leader Harry R. Bridges, announced plans to shut down the shipping industry along the entire Pacific Seaboard. The strike was set for March 23rd, 1934 – the day before the Mount Davidson Cross-lighting ceremony. History books now describe this union walkout as one of the most divisive and significant events of the Great Depression. Is it just a coincidence that FDR convinced the Longshoremen to postpone their walkout and try arbitration just two days before the cross dedication? What we do know is that President Roosevelt lit the world’s largest cross because this forgotten woman asked him to – as 50,000 San Franciscans peacefully watched on the slopes of Mt. Davidson.

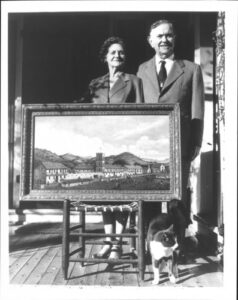

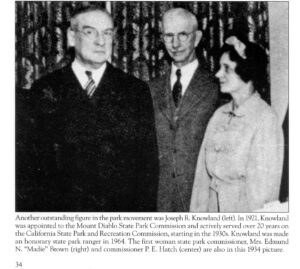

Madie (pictured above in 1929 and again in 1955, standing on the right) did much more, however, than get this monument dedicated by the President. An ardent nature lover, she was the one who organized a citywide preservation effort to make Mt. Davidson a public park. Because of Madie, we are able to experience today what the founder of the sunrise services, James Decatur, enthusiastically described 80 years ago. “As the group found themselves deeper in the wood…peace and quiet were so profound that it seemed almost unbelievable that the noise and roar of a great city was only a few minutes behind them. The solitude of the forest …conveyed a sense of vastness quite as real as one would experience among the age-old monarchs of the High Sierras…The undergrowth and flowers looked as if they might have been there for centuries…The path wound around the slopes so perfectly that the ascent was hardly noticeable… (At the summit was) a clear vision of the great panorama that spread before the eye… on the far eastern horizon stood the bold figure of Mt. Diablo… to the west …could be seen the boundless Pacific, with the headlands of Point Reyes and Point San Pedro forming widespread arms of welcome to those who enter the Golden Gate. (Below were) tall monuments of steel and concrete wherein were housed thousands of busy minds…Myriads of moving objects were, without doubt, hurrying hither and thither, all within vision of Mt. Davidson, yet the noise and tumult of it all was absent.”

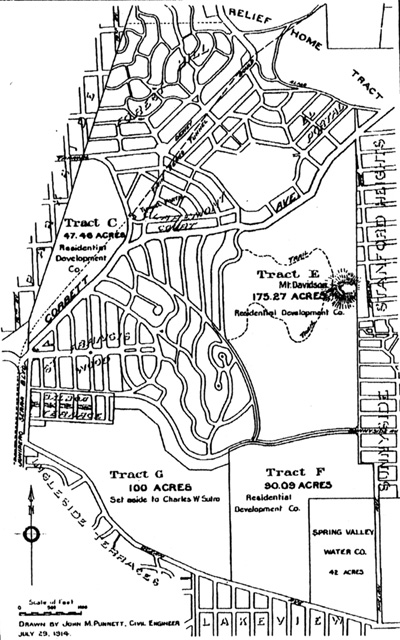

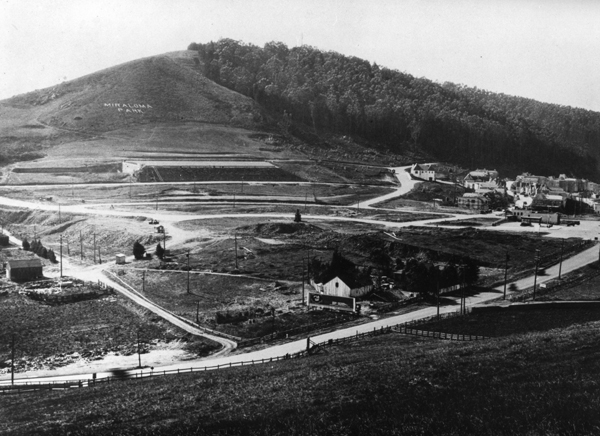

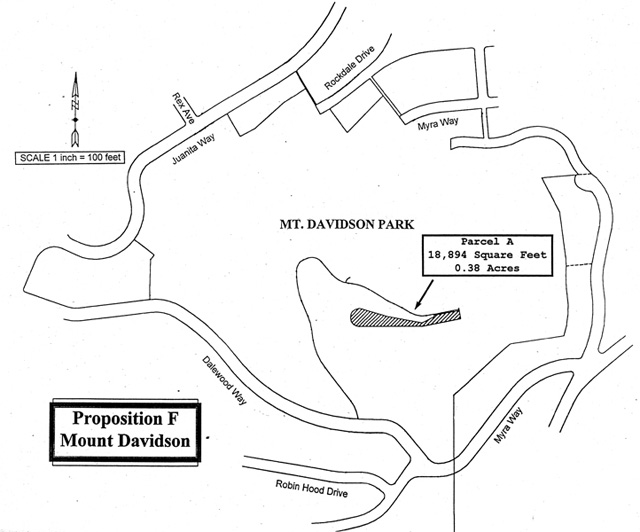

The Sierra Club initiated renaming this popular hiking area for the pioneer scientist, surveyor, and charter member, George Davidson, in 1910, after developer A.S. Baldwin purchased the property from Adolph Sutro‘s estate and built trails to the summit, shown on the map to the right, for the “pleasure of the public.”

Inspired by the hike and view, James Decatur got permission from Baldwin to build a temporary cross for an Easter sunrise ceremony in 1923. More than 5,000 attended and its popularity resulted in plans to make it an annual event. But as Baldwin began building homes further up the slopes of Mt. Davidson three years later, Madie Brown, became “alarmed by the destruction,” and made a plea for preservation to the Commodore Sloat Elementary School Parent-Teachers Association. “The subdividers’ axe and steam shovel are destroying in ruthless fashion the beauties of nature on our beloved Mt. Davidson,” she cried. We must “preserve for San Francisco this wooded hill to provide our school children with the environment for nature study; the Boy Scouts with an outdoor playground for hikes and overnight camping; the Easter pilgrim for a place of worship on its summit at dawn; and the visitor with unsurpassed views from the highest point in the city!” Madie was appointed chair of the Mt. Davidson Conservation Committee. Gathering historical data, maps, and an appraisal for the property, this State Park Commissioner may have been the first to say no to San Francisco’s powerful building industry.

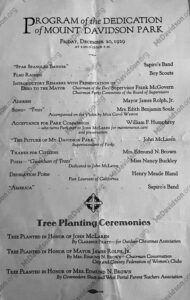

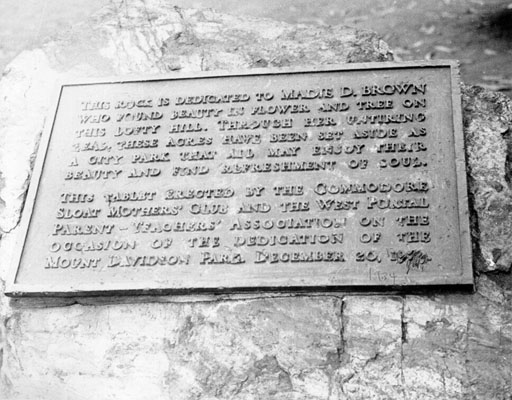

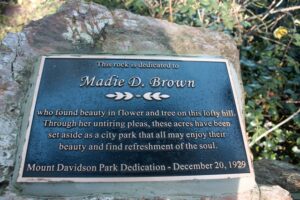

Mrs. Brown proceeded to intuitively write the rulebook many now use for grassroots organizing. The P.T.A. mothers and their children sent wild flowers from the mountain to individuals as pleas for support. Exhibits were set up at flower shows and schools. The 15,000 members of the City and County Federations of Womens Clubs voted to support the cause. Dressed in earnest with her stylish hat and suit, Madie set up interviews with the prominent and powerful to persuade them to join her cause. Publicity was secured in the press and shown on newsreels at the theaters. Soon Mayor “Sunny Jim” Rolph and Margaret Mary Morgan, the first woman elected to the Board of Supervisors, prominent citizens, improvement clubs, and civic organizations were joining the citywide demand for the protection of Mt. Davidson. After a three-year campaign, the S.F. Chronicle reported that, “due to the effort of a nature loving woman… the tree clad slope and crest of Mount Davidson, rich in sentiment and historic association for San Francisco was now permanently preserved for the pleasure of the people.” Twenty acres of the forested western slope of Mt. Davidson was purchased by the City and dedicated as a public park on December 20, 1929, the 84th birthday of the City’s Superintendent of Parks, John McLaren.

- Park Dedication Program found inside Cross time capsule on April 1, 2023

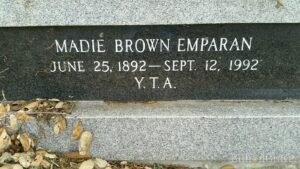

A lifelong historian, political activist, and conservationist, Madie Brown was born in Alabama on June 25, 1889 as Madie Diggett. She married Robert Brown, the owner of Brown Majestic Electric Appliance, and had three children. In 1933 she was living at 15 Montalvo Ave. in San Francisco’s Forest Hill neighborhood and in view of Mt. Davidson. By 1934, Madie was serving as the first female member of the State Park Commission.

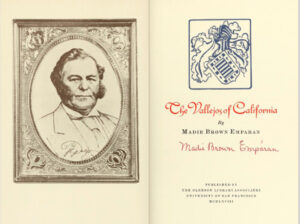

By 1947, she was the Curator of the Vallejo home in Sonoma and married to Richard Raoul Emparan, General Vallejo’s grandson.

Her biography of the Vallejos in California was published in 1968 after 20 years of research. Madie also planned a work on John McLaren, the Scottish botanist who designed Golden Gate Park. Her notes for the project are in this collection. She was also active in the John Muir Association’s efforts to have a forest in King’s Canyon National Park named for John Muir (1941). Richard passed away in August 1975 at the age of 89. Madie continued to live in Sonoma until her death in 1992. They are buried in Mountain Cemetery in Sonoma.

Controversy is integral to public art and to San Francisco. Three years after the Mount Davidson Cross was built, master artist, Beniamino Bufano, offered to place a taller St. Francis sculpture atop Twin Peaks. The Art Commission, in a narrow vote, “disapproved without prejudice” his WPA proposal to erect a 180-foot high stainless steel statue that would have dwarfed the cross. Now a giant red and white tower adorns the mountain named after Adolph Sutro. Taller than the city’s skyscrapers and the Golden Gate Bridge, and nine times the size of the Mt. Davidson Cross, now shrouded bu trees planted by kindergartners a hundred years ago; a judge ruled that the location of the cross on public property and the City’s highest point showed a preference for Christianity. Ironically Madie’s fight to stop private development of the peak and preserve it, as public open space, would be used as a reason to argue for removal of a monument dedicated to bringing the golden rule to business.

Sixty-five years after its donation to the City, the 6-acre summit of Mt. Davidson Park was proposed for sale to settle to lawsuit. After a petition drive by the Friends of Mount Davidson Conservancy, only .39 acres of the park was put on the auction block with the fate of the cross left to the highest bidder. San Franciscans voted to ratify the sale to the Council of Armenian Organizations of Northern California in order to preserve the historic monument. On January 20, 1998, the City officially divested itself from the property. Surviving a second trip to the CA Supreme Court and back, the summit remains open to the public and the cross continues to be lit on Easter eve, as it was by President Roosevelt in 1934. The plaque honoring Madie has since been stolen from the top of the trail to Inspiration Point. In its place is a court-ordered sign about the removal of the religious monument from public ownership.

A replacement plaque was installed in 2010.

See the event: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jbk5NQM9q2o

Men surveyed, named, bought, sold, developed, litigated and used Mt. Davidson for political gain, but a woman preserved it for the millennium. Madie did not use her victory as a stepping-stone for political office, leaving instead an unselfish legacy of neighborhood activism, women’s political action, and environmental protection. She never owned the mountain, nor is it named for her, but Madie Brown is the one that dared to dream that this lovely spot on the city’s highest hill could be saved for the public to enjoy today in the midst of what is now the 2nd densest city in America. Marking the outermost boundary of western civilization, for some the monument at its top is a politically incorrect relic of manifest destiny. But others embrace it for surviving with them through the worst times they ever faced. Visible from my living room window, whether it is reflecting a beautiful sunrise or dancing with the fog, the view of Mt. Davidson nurtures my senses and my soul. For me the monument at its summit is a peaceful and contemplative icon to focus upon before facing the “myriads of moving objects” outside my urban door. I feel lucky that in my own front yard is one of the many public artworks created to nurture San Franciscans through the Great Depression. Because of Madie, it also remains to remind us that the future of the American dream is not just about faith in God or capitalism, but our practice of universal ethics such as the Golden Rule.

- Poem dedicated to Mt. Davidson for the park dedication found inside the cross time capsule April 2023

- Madie Brown first female State Park Commissioner