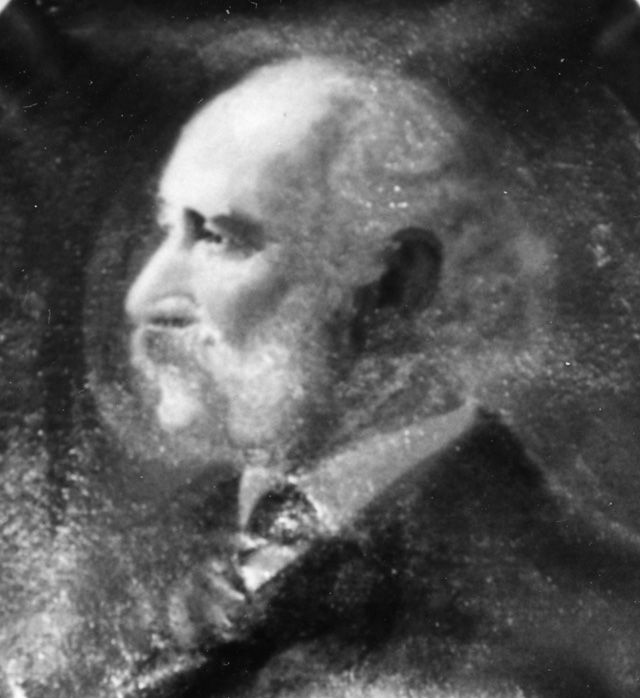

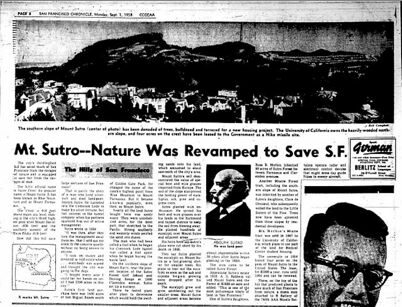

Adolph Sutro

Adolph Heinrich Joseph Sutro was born at Aix-la-Chapelle, Rhenish Prussia on April 29, 1830. The second eldest of 13 children, he and most of his siblings emigrated to Maryland from Germany with their widowed mother in 1850. California’s Gold Rush brought him west to San Francisco a year later, where he became a tobacco merchant. Nine years later, after the discovery of silver in the Comstock Lode, he headed for Nevada where he quickly realized that the mining methods in use were outmoded, inadequate and dangerous. Mount Davidson above Virginia City, Nevada, and written about by Mark Twain in Roughing It, was said to be cursed after Edgar Allen and Hosea Grosch died shortly after being the first to discover the silver in it. Sutro conceived the idea of a tunnel under the Comstock Lode to eliminate the rising hazards of fire, drainage, and ventilation and which, incidentally, could be used to transport ore directly to the mills recently constructed along the Carson River. He would make his fortune with that tunnel and use it in 1880 to buy 1,200 acres of Rancho San Miguel, including the hill now known as Mount Davidson in San Francisco and the present Mount Sutro which he named Mount Parnassus. He would continue to add to his land holdings until he owned 2,200 acres of the city, stretching from Bakers Beach and Lincoln Park to the shores of Lake Merced.

Gallery

In February 1865, Adolph Sutro came to William Ralston, the builder of the Palace Hotel and Bank of California, with a plan to build a tunnel deep into Mount Davidson. Mark Twain wrote, “The Sutro Tunnel is to plow through the Comstock Lode from end to end, at a depth of two thousand feet, and then mining will be easy and comparatively inexpensive; and the momentous matters of drainage, and hoisting and hauling of ore will cease to be burdensome.” Ralston agreed to the request and with signed agreements from twenty-three Comstock mines, Sutro headed east to raise the $3 million he needed to begin this tunnel. (Courtesy www.californiapioneers.org)

In July 1876, Congress passed the Sutro Tunnel Act, which gave him federal right-of-way, liberal mining rights along the tunnel’s seven-mile length, and a large plot of land at the tunnel’s entrance. Sutro ran for the United States Senate in every election from 1872 to 1880, drumming up money and preaching the wonders of the tunnel. For nearly a decade, the work progressed until completion in the summer of 1878. In October 1879, ex-president Ulysses S. Grant led a victory parade through the tunnel. It still remains as one of the engineering wonders of the world. (Photo Courtesy Glenn Koch.)

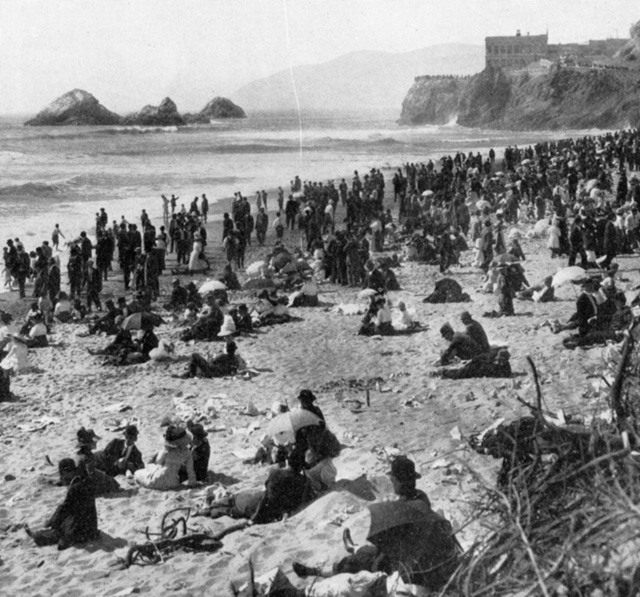

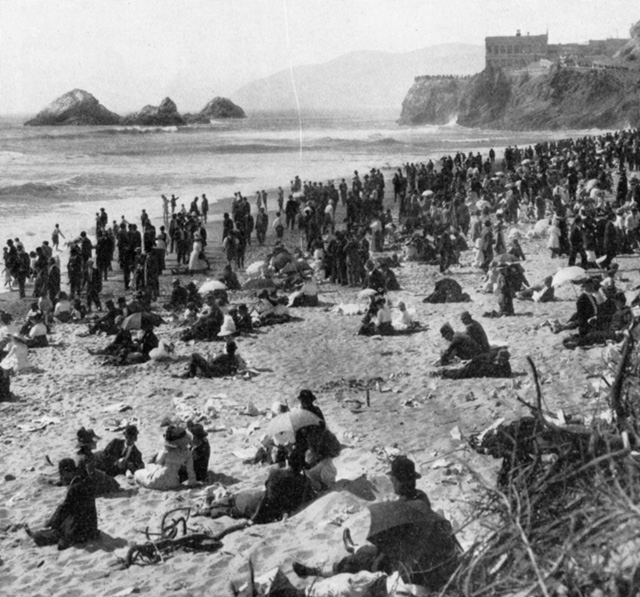

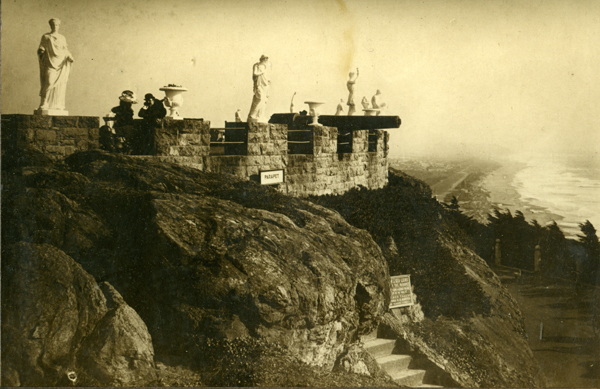

Adolph Sutro, San Francisco’s philanthropic mayor from 1894-1896, enjoyed riding horses with his daughter Emma (one of the first women medical students at the University of California) out to enjoy the miles-long view of the Pacific shoreline. He decided to build his last home here, constructing it to the rear of this granite parapet built on the very rim of the heights, above the Cliff House, adorning it with replicas of Greek statuary and urns. The public was welcome to stroll his extensive formal gardens boasting terraces, lawns, shrubs, grottos and arbors, with a profusion of imported exotic plants and trees planted in a shipload of soil he imported from Australia, – but smoking was not permitted. It was here that Sutro played host to everyone from Oscar Wilde to President Benjamin Harrison. (Photo Courtesy Ken Hoegger.)

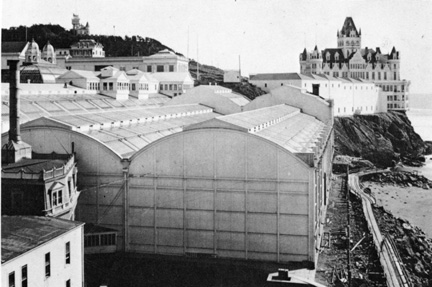

Sutro’s Cliff House restaurant survived the 1906 Earthquake but burned down a year later. It was rebuilt, pictured here at Ocean Beach in 1915, behind Sutro Baths, the world’s largest swimming pool, that he opened in 1896 to give the average San Franciscan a place where they could afford to have fun. (Photo Courtesy Margie Whitnah.)

Additional images of the Sutro Baths under construction:

Joseph R. Bisho Sr. standing on the beach with the Cliff House in the background in 1920 on a visit from Hawaii. His son will grow up in San Francisco and raise his family west of Twin Peaks. (Photo Courtesy of Dave Bisho.)

The naturalist poet, Joaquin Miller, who achieved great popular and critical success with his Songs of the Sierras, was enthusiastically planting trees on “The Heights” in the East Bay when he envisioned the beauty that might be created by trees on the San Miguel Hills and suggested the plan to Adolph Sutro. Sutro was celebrated as the Father of tree planting in California on the state’s first Arbor Day on November 26, 1886 which he exemplified by enlisting schoolchildren to plant trees on Mount Davidson, Mt. Sutro, Yerba Buena Island, Fort Mason, and the Presidio.

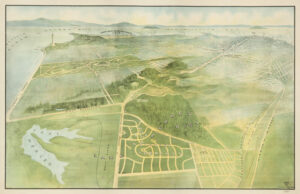

By the time of his death on August 8, 1898, Sutro’s forest extended four miles from Mt. Sutro south to Mt. Davidson as seen in this 1915 advertisement for buying homes in Ingleside Terraces.

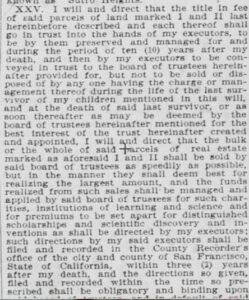

Sutro left his estate to his children, however, his will (excerpt below) stipulated that none of the land could be sold until the death of the last child, and the proceeds would go to a charitable trust.

His heirs challenged the will and persevered even longer than Sutro did to get his tunnel built, to obtain a California Supreme Court ruling that overturned it in 1919, twenty-one years after Sutro’s death. They sold acreage to developer A. S. Baldwin who built new residential neighborhoods on the slopes of Mt. Davidson.

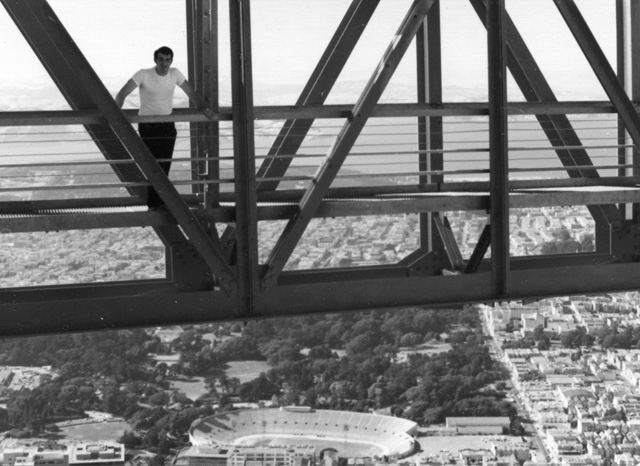

The view of Kezar Stadium from atop the 977-foot high television transmission tower built in 1972 and named for the former owner of the hill, Adolph G. Sutro, whose home, La Avenzada, designed by Harold G. Stoner was destroyed to build this tower. (Courtesy Ron Davis.)

Looking up one of the Sutro Tower legs before it is closed off.

Sutro’s Forest on Mt. Sutro led to an effort to preserve it as open space.

On nearby Mount Olympus, the exact center of San Francisco, overlooking Market Street, Adolph Sutro had erected his own skyline beacon – the statue Triumph of Light (a concrete copy of a Belgian work of art showing Liberty victorious over Despotism) in 1887, telling the schoolchildren at its dedication, “May the light shine from the torch of the Goddess of Liberty to inspire our citizens to good and noble deeds for the benefit of mankind.” (Courtesy Ron Davis.)